Hey, everyone! Lindy here with my first blog post. I’m so excited to see this community grow and learn about those who, like our team, want to make a difference. So, before I delve into your stories that I’ll hope you’ll share with us, here’s part of mine:

I’ve learned (in my short 22 years) that there are few things more powerful than empathy – it inspires vulnerability without exposure, compassion without expectation, action without reaction. It seems that empathy works beyond our physical, emotional, and even spiritual expectations, accessing the unifying quality that connects all of us: our humanity. When I realized this, that our humanity is woven and maintained by the powerful ties of empathy, I knew we (all humans) were experiencing a crisis of ignorance. Too few of us are awake to the possibilities and the power of our empathetic connections, so many assume that they are powerless as individuals, and too many assume that their resources entitle to them to a destiny that is somehow different from the one that belongs to the rest of the human race.

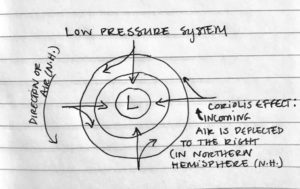

In my last year at Amherst College (go Mammoths), I wrote a thesis on Native American literature – specifically creation narratives. Did my fellow geology majors tease me that writing a thesis for my English degree was a cop-out, especially as I planned a Fulbright fellowship that would take me to the Arctic Circle to study climate change? Sure. But, to me, the issues facing Native Americans – the issues facing any marginalized nation, community, or social group – are intimately connected to environmental stress and will only worsen with climate change. I felt it was imperative to start understanding how our perceptions of climate change affect the way we cope with adaptation and mitigation. Over the course of the last national election cycle, many of us have, unfortunately, seen that some of the most powerful individuals in the American government are climate skeptics or, if they do perceive that the climate is changing, they insist that human beings have no hand in the warming process. Or, worse: they accept both facts – the climate is changing and humans are increasing the rate and magnitude of that change – but that these facts are not pressing enough to divert some of the oxygen in Washington and talk about how to fix it – maybe they’re right, since superstorm hurricanes like Sandy and Harvey are low-pressure systems, after all (that was a geology/meteorology joke and I won’t apologize for it).

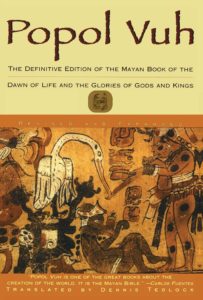

Anyways, as I witnessed the importance of perception in how we address and interact with this spaceship we call Earth, I knew that delving deeply into creation narratives would fundamentally shift the way I thought about my own relationship to the planet. This line of inquiry would, perhaps, give me some fodder to reconcile and explain – to myself and others – how terribly detached we’ve become fr om each other and from the land that nurtures us. And, indeed, the seeds for this reconciliatory shift exist throughout Native creation narratives. They’re buried in the Mayan Popol Vuh, in lamentations for the lost “brothers” and the human “shattering” at the dawn of time when the Mayan people disseminated across the land; they germinate in the structure of the Iroquois Confederacy, which values community above physical assets, condemns isolation and emphasizes the importance of cooperation; these seeds of truth and remembrance even sprout in the present moment (though, as I argued in my thesis, all of these stories are part of one “ancient-present” moment) through the Penobscot Nation’s perception of land rights and their ongoing legal battle with Maine’s government over sustenance fishing rights in the Penobscot River.

om each other and from the land that nurtures us. And, indeed, the seeds for this reconciliatory shift exist throughout Native creation narratives. They’re buried in the Mayan Popol Vuh, in lamentations for the lost “brothers” and the human “shattering” at the dawn of time when the Mayan people disseminated across the land; they germinate in the structure of the Iroquois Confederacy, which values community above physical assets, condemns isolation and emphasizes the importance of cooperation; these seeds of truth and remembrance even sprout in the present moment (though, as I argued in my thesis, all of these stories are part of one “ancient-present” moment) through the Penobscot Nation’s perception of land rights and their ongoing legal battle with Maine’s government over sustenance fishing rights in the Penobscot River.

I am not suggesting we adhere to some maligned argument for the “ecological Indian,” (that trope can stay firmly in the past where it belongs (though it really should never have been there in the first place)). I am simply suggesting that there are ways of viewing each other and the environment in which there is no separation between the two. As biologist and author, David George Haskell, writes:

“We’re all — trees, humans, insects, birds, bacteria — pluralities…Because life is network, there is no “nature” or “environment,” separate and apart from humans. We are part of the community of life, composed of relationships with “others,” so the human/nature duality that lives near the heart of many philosophies is, from a biological perspective, illusory.

We are not, in the words of the folk hymn, wayfaring strangers traveling through this world. Nor are we the estranged creatures of Wordsworth’s lyrical ballads, fallen out of Nature into a “stagnant pool” of artifice where we misshape “the beauteous forms of things.” Our bodies and minds, our “Science and Art,” are as natural and wild as they ever were.”

To expand on this thought, I’ll point out that climate change does not discriminate based on gender, race, ethnicity, etc.; climate is simply the long-term average of weather patterns abiding faithfully by the natural laws of our universe – it is we, human beings, that impose climate discrimination. We do this chiefly through the economy – I cannot count the times I’ve heard it said that only when wealthy people begin to lose money as a result of climate change will we see a change in philanthropic, industrial, and governmental investments in preparing our world for what’s to come. But, on the more hopeful side of this industrial coin, we – you, me, literally everyone – can vote against this type of discrimination everyday with our dollars. We can choose to give our money to companies that promote sustainability; we can stop buying food from unsustainable sources like the meat and dairy industries (yes, that was my one and only plug for veganism… besides the accompanying picture); we can choose to invest in a future that does not discriminate against those without the financial means to live a happy, healthy, and safe life by donating to renewable energy charities *cough*. In the cycle of supply and demand, there is no reason why we cannot come together and create a more egalitarian consumerism – we need to make an empathetic shift so that the things we demand are happy, healthy, and safe.

As anthropologists suggest, “well-being is a process…a set of relations between people, and between people and places, at particular times.” It is not enough to install sea walls, create fire-mitigating defensible spaces, build flood-resistant housing, or even climate change policy – in order to adapt to this changing world, we need to build community. When community is intact, the system supports itself, rather than relying on temporary response measures. When community is intact, then adaptation becomes transformation; individuals take the future into their own hands without fearing failure because many hands are there to catch them if they should fall.

This is where inourhands.love comes in. What excited me to build IOH with the rest of the team was not so much the potential it had to revolutionize the world of non-profits (though, that’s pretty cool, too), but rather the potential it has to build community. And, more importantly, inourhands.love has the potential to build this community for a greater good; to rally people around positive change rather than dissension or political vitriol. Think about it this way: when natural disaster strikes, the world bands together and pulls the affected area out of the rubble. It shows compassion and generosity beyond anything we see on a daily basis. Now, think what we could accomplish if we showed that kind of compassion to communities who struggle with issues on par with a natural disaster, but are currently without national or international recognition. That is, think what would happen if we started building each other up before we were torn down. With your help. inourhands.love can make that happen. Help us rediscover empathy.

Thanks for reading! You can find me on any of the following platforms:

Website: www.lindylabriola.com

Instagram: @lindy_lab

Twitter: @LindyLabriola

LinkedIn: Malinda (Lindy) Labriola

Sources:

Anthropology quote: http://www.tandfonline.com/eprint/iTgQqMtQjG8dvCzMp8vd/full

Vegan Protein Chart: https://fanaticcook.com/2015/11/24/vegan-protein-chart/

Haskell Book: https://www.amazon.com/Songs-Trees-Stories-Natures-Connectors/dp/052542752X